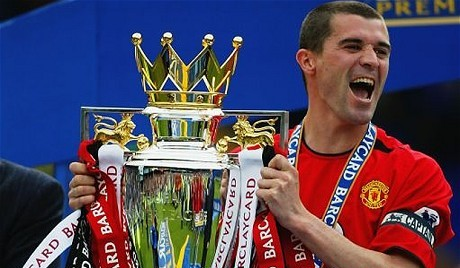

Roy Keane – Robot, Madman, Winner

Honours: 1993-2005 – 480 appearances (51 goals); Premier League 1994, 1996,

1997, 1999, 2000, 2001, 2003; FA Cup 1994, 1996, 1999, 2004; Champions League

1999; Inter-Continental Cup 1999

Quote: “If I was putting Roy Keane out there to represent Manchester United on a one against one, we’d win the Derby, the National, the Boat Race and anything else. It’s an incredible thing he’s got.” – Sir Alex Ferguson

Greatest moment: Despite knowing he would miss the final, he still inspired United to a brilliant comeback win against Juventus

In the Manchester United Best XI because: he was the most influential player of his generation, whose restless anger and presence in midfield galvanised all those around him.

“NO ONE WILL remember me in 20 or 30 years time. In comparison to George Best, I won’t be remembered. And that’s fine – why should I be?”

It is the spring of 2001, and I’m sitting opposite Roy Keane in a photographer’s studio in Manchester. At the time he is the best player in Britain and the reigning Footballer of the Year, so I am more than little surprised to find myself having to convince him of his standing in the game.

“Because you captained one of the greatest club sides of all time,” I tell him.

“Ah, there’s been a lot of great United captains: Steve Bruce, Bryan Robson, Eric

Cantona…”

“But none of them enjoyed your success. You captained United to the treble.”

“You tell me what that means? That was two years ago. That’s the problem, people are always looking back. United won the European Cup in 1968 and didn’t stop going on about it until we won it again.”

“They would always talk about the great teams of the Ron Atkinson era who didn’t win anything… OK, they won the FA Cup a couple of times. People need to set their standards a bit higher and not live in the past.”

“Who ever said I want to be remembered anyway? Why should I worry about what people think about me in the future? I might be dead tomorrow.”

It was this bluntness, lack of sentimentality and searing honesty that made Keane the most successful captain in United’s history and has ensured, even if he doesn’t care, that he will be always be remembered. Manchester United’s relentless success throughout most of the ’90s and into the new millennium was based upon Keane’s driven character. Keane was Sir Alex Ferguson’s voice on the pitch; together they shared an insatiable hunger to keep on winning. It is why Ferguson, after twenty years at Old Trafford declared, “Keane is the best I’ve ever had here.”

“If I was putting Roy Keane out there to represent Manchester United on a one against one, we would win the Derby, the National, the Boat Race and anything else. It’s an incredible thing he’s got.”

A complex and intense character, Keane was always simmering, always striving for perfection. He set the standards at United, even when they seemed impossibly high. He once acknowledged his image was that of “the robot, the madman, the winner.” This obsession with winning gripped him long before he arrived at United. “I could never accept losing. It’s like at school, or at Rockmount [his schoolboy team]. The trainers would be going, “Relax, Roy,” but no, that’s not me. Mad, I know.”

The small details mattered to Keane. On his first day of pre-season training with United in 1993 he ordered a taxi to drive to the Cliff training ground, and followed behind in his own car to guarantee he would not get lost. He also arrived an hour before anyone else. In the following years when a new player like Mark Bosnich arrived late for their first day he made them aware he was disgusted they had not made the same effort as him.

On the pitch he appeared to be in a constant state of rage, Gary Neville has said he got exhausted just looking at him, and wondered how he didn’t have a heart attack. Neville recalls being abused for taking one – yes one – extra touch of the ball before crossing it. “It was like having a snarling pit bull in your face.”

“Keane’s greatest gift was to create a standard of performance which demanded the very best,” said Neville. “You would look at him busting a gut and feel that you’d be betraying him if you didn’t give everything yourself.”

“Aggression is what I do,” Keane admitted. “I go to war… You don’t contest football matches in a reasonable state of mind.”

But revering Keane as a leader shouldn’t obscure his quality as a player. He wasn’t in the team simply to motivate others; he could play too. He might not have been pretty, with his scurrying running style, straight back and hunched shoulders but he had an incredible presence in the centre of midfield. Keane did the simple work brilliantly. He was an expert at snuffing out attacks with his expertly timed tackles (he once admitted to me he would see players pull out of them against him), then wisely distributing the ball; he kept possession with ease, rarely wasting the ball and could often dictate the tempo of games on his own. His stamina could not be matched and would take him up and down the field, surging forward to score at one end before tackling back at the other.

“I’m not capable of something magical, so my strength is my work-rate, and if I don’t have that I may as well pack the game in,” he once said. “I keep going when others maybe don’t.”

As a teenager Keane wrote to several clubs in England asking for a trial but not to Manchester United because he didn’t think he would ever be good enough for them. However, in 1990, at the age of 18, his performances for the Irish side Cobh Ramblers persuaded Brian Clough to sign him for Nottingham Forest for £47,000. He made an immediate impact in his first season establishing himself as a regular, winning his first cap for Ireland and collecting an FA Cup runners-up medal after losing in the final to Tottenham Hotspur.

The United scout Les Kershaw was at Anfield in August 1990 to witness Keane’s début. He had gone to watch Liverpool, but was captivated by the young Irishman. “I have seen a player, a real player,” he told his boss back at Old Trafford. Ferguson watched him once and declared, “We must have him.” But United would have to wait another three years, and pay a British record transfer fee of £3.75 million, before they could ward off a resurgent Blackburn Rovers and bring him to Old Trafford in the summer of 1993.

The Irishman turned a good team into a great one. United had won the Premier League the year before, but with the addition of the midfielder, they added the FA Cup to the title to complete the club’s first Double. Keane was an integral part of a side many regard as United’s best ever. He soon became United’s most important player, making light of Paul Ince’s departure, to help lead United to another Premier League and FA Cup double in the 1995-96 season. In the FA Cup final against Liverpool Eric Cantona naturally drew the most praise for his dramatic late winner, but Ferguson declared Keane was the real man of the match for tirelessly smothering out any threat from Robbie Fowler and Steve McManaman.

Another Premier League title was added in the 1996-97 season, before Eric Cantona’s retirement saw Keane, still only 25-years-old, handed the captaincy. After only a month wearing the armband and frustrated at United playing “crap” and losing 1-0 to Leeds, he flicked a leg at Alf Inge-Haaland, but caught his studs in the Elland Road turf and snapped his cruciate ligament. He would miss the rest of the season, and without him United relinquished the title to Arsenal.

Keane’s year sitting on the sidelines turned in to one of both indulgence and enlightenment. Keane had always liked a drink, he even partly blamed it on picking up the injury at Leeds, admitting to getting in to a drunken fight with some fellow Irishmen at a hotel two days before the game. “My night of drinking had taken it’s toll,” he would write in his autobiography.

Since he had arrived at Forest the naturally shy Keane admitted he had drunk heavily, and had several scraps. It was all part of a night out. “That was the norm back then, we used to get wrecked,” he has said.

At first, the lack of football only accelerated his drinking. “I was out on the piss every night,” he said. “[It was] totally ridiculous. I was doing a lot of stuff I shouldn’t have been doing, daft stuff like jumping over hedges and cars. I’d sometimes come in the next day and I couldn’t move for my knee.”

But as he went through his recovery he realised he had to change and cut out the drinking. “I’d watch the lads finish training, and they’d shoot off like the building was on fire, like they couldn’t get away quick enough. I said to myself, ‘If I do get back there, I’m going to work on the things I need to work on’.”

In the summer of 1998, on the brink of his comeback, I spoke with Keane at the Cliff. He seemed like a man in a hurry, as though he wanted to make up for lost time. “I’m more hungry about the game now, being out helped me appreciate my position more.”

However, there was self-doubt too. “A day has not passed where I haven’t thought ‘Can I ever be the same player again?’”

He would prove he was the same player, probably even better, as in his first full season as captain he made the most appearances of any outfield player, was voted the club’s Player of the Year, and above all led United to the treble of the Premier League, FA Cup and Champions League. Throughout the Treble year Keane was the difference, and nowhere was this better displayed than in the defining game of his career against Juventus in the second leg of the Champions League semi-final at the Stadio Delle Alpi.

After drawing the first leg 1-1, United found themselves trailing 2-0 after only 11 minutes. It appeared as though United’s hopes of wining the Champions League – and the Treble – were over. Luckily, no one told Keane. Though he was faced with one of Europe’s strongest ever midfields, comprising of World Cup winners Zinedine Zidane and Didier Deschamps and Dutchman Edgar Davids, Keane chased a seemingly lost cause, even after being shown a yellow card which meant he would be banned from the final should United reach it.

“I didn’t think I could have a higher opinion than I already had of the Irishman but he rose even further in my estimation,” Sir Alex Ferguson wrote in his autobiography. “The minute he was booked and out of the final he redoubled his efforts to get the team there. It was the most emphatic display of selflessness I have seen on a football field. Pounding every blade of grass, competing as if he would rather die of exhaustion than lose, he inspired all around him. I felt it was an honour to be associated with such a player.”

Gary Neville has admitted the players looked at the efforts of Keane, and realised they could win after all. Keane started the comeback himself, glancing in a corner from David Beckham before sprinting back to the centre to get the game restarted. Goals from Dwight Yorke and Andy Cole then secured United’s place in the Champions League final for the first time in 31 years.

On the jubilant flight back to Manchester, Ferguson confided in United’s head of security Ned Kelly: “I never thought I would say this, but he’s actually a better player than Bryan Robson.”

“No matter how many people tell me I deserve that Champions League medal, I know I don’t,” said Keane in his autobiography. “In fact, you could argue my indiscipline came very close to costing us the treble.”

In the following season Keane cemented his position as the country’s leading player, captaining United to another title and finishing the season by winning the Footballer of the Year award.

I was at the Royal Lancaster Hotel in London to watch him accept his trophy and he looked distinctly uncomfortable, like an awkward teenager, as he gave his acceptance speech.

“Oh Jesus, that was the most nervous I have ever been,” he would later tell me. “Everyone was being so nice, and saying lovely things about me that I felt really embarrassed. I just thought, ‘Jesus! Get me out of here!’ Some people, with more confidence, might have liked it, but it really wasn’t my thing.”

Keane was always the antidote to football’s burgeoning celebrity culture, famously willing to criticise the “prawn sandwich” corporate fans that didn’t give the club enough support at Old Trafford. He was the anti-David Beckham. He did not have an agent, and never courted attention. “I’m not comfortable with the adulation,” he once told me. “Some might enjoy it, but I don’t. I like the respect you get for being a

footballer, but the rest is a load of crap. I wouldn’t idolise a footballer.”

Keane was always a bit different, something of a loner, for while he engineered a team spirit in his United sides, he also said he wouldn’t send his teammates a Christmas card, ask them out for a drink, and didn’t have any of their phone numbers.

Gary Neville tells a story of texting Keane with his new mobile number, and receiving a text straight back from him, which said: “So what.”

While Keane could be blunt, I always enjoyed interviewing him. Even if there was always a sense of trepidation to it as well, for he didn’t suffer fools, and would let you know about it, from his vice-like handshake to his intense all-knowing stare. A photographer I worked with once asked Keane to growl in to the camera. “I’m a footballer, not a fucking actor,” he replied.

But Keane could be charming and affable too, far removed from the menacing veinbulging figure wearing a red shirt. Once he got going he could actually enjoy himself too, on one occasion rather than cut short an interview with me, he instead asked his wife Theresa to pick up their three children from school. The truth is he was a dream to interview, because he was always brutally honest, he never ducked a question, and simply gave it to you straight.

The last time I interviewed him was in April 2001, the morning after United had lost the first leg of the Champions League quarter-final to Bayern Munich. I feared he might be surly and uncooperative, but the defeat had left him in a reflective mood. Even though United were on the brink of winning a third consecutive Premier League title, the failure to get back to the Champions League final troubled him. He had things he wanted to get off his chest.

“We have to be careful to think that our success is going to go on and on. We have to start dominating Europe as well as the Premiership. It is up to the manager to know when to move people on,” he said. “I have seen United players getting complacent, thinking they’ve done it all and getting carried away by a bit of success. All you have to do is drop your standards by 5 per cent or 10 per cent and it’s obvious, especially in Europe. You can see it in training when players just go through the motions. You can’t do that, you always have to give your best. It’s up to the manager to spot it, maybe I’ll help him.”

The interview was the cover story for FourFourTwo magazine, but after being published the tabloids all picked it up, and The Daily Mirror splashed it across their back page as “The most explosive interview of the year.”

I was told Ferguson was furious at the headlines and had hauled Keane in to his office.

In the final years of his Old Trafford career, Keane would alter his game, making less surging runs, and instead sitting in the centre of midfield, organising his teammates and expertly distributing the ball.

It was enough to captain United to another Premier League title in 2003 and the FA Cup in 2004. As his manager observed: “He is a far more measured player now, more of a thinking player. Five years ago, maybe he lived on his raw energy. Now you see a mature player. He is a player at his very peak.”

Having recovered from a hip injury, which was thought might have even ended his career, and could require a hip replacement in retirement, Keane took more care of his body, embracing yoga sessions and hot stone massages.

But it was never going to quell the fire inside him. He would be sent off 11 times for United, the first in 1995 and the last in 2004, with the most infamous being when he took his revenge on Alf-Inge Haaland in the Manchester derby at Old Trafford in April 2001. He had never forgiven the Norwegian for standing over him and accusing him of faking his cruicate injury at Elland Road. In between the two incidents, I asked Keane

if he carried a grudge against Haaland? “No, not me,” he said, but at the time, I wrote “his smiling eyes say differently.”

In his autobiography, Keane writes about the motivation behind his horrific thighchallenge on Haaland. “I’d waited long enough. I fucking hit him hard. The ball was there (I think). Take that you cunt. And don’t ever stand over me sneering about fake injuries.” This account would earn him a five-match ban.

It was in his final full season in March 2005 inside the tight tunnel at Highbury that possibly the defining image of Keane’s career occurred. Lining up to face Arsenal, the reigning champions and Invincibles of the previous season, Keane saw his nemesis Patrick Vieira attempting to intimidate Gary Neville.

An outraged Keane shouted, “You, Vieira, come and pick on me.” With his eyes blazing, he pointed to the pitch, and added “I’ll see you out there.” Keane had set the tone for the game: ‘Stick behind me lads, we’ll sort this’ was his message. He played the whole game with a controlled anger and on this occasion didn’t even get booked as he inspired United to a 4-2 win over the champions.

Keane’s restless anger, once such a vital part of his armour, would eventually lead to his downfall. In the autumn of 2005 he was invited on to MUTV to discuss United’s 4-1 defeat at Middlesbrough, even though he hadn’t played. It was a strange choice, never destined to end well. Keane proceeded to do what he always did, and told the brutal truth. Having seen United miss out first to Arsenal and then Chelsea in the last two league campaigns, and seeing little evidence this was about to change in the current season, Keane’s pent-up anger at his young teammates boiled over. The show never made it on to the air, having first been shown to the United Chief Executive David Gill, who decided to ban it, but details inevitably leaked.

Keane had broken with protocol by singling out individual players. It was reported he said of Rio Ferdinand: “Just because you’re paid £120,000 a week you think you are a superstar”; Darren Fletcher is spoken about with contempt: “I can’t understand why people in Scotland rave about Darren Fletcher”; Kieran Richardson is described as “a lazy defender,” while Alan Smith’s role as a makeshift midfielder prompts the observation: “He doesn’t know what he is doing.”

It took Ferguson two weeks to reach the reluctant, but inevitable, decision that Keane had gone too far and would have to go.

On the morning of November 18, 2005, Keane was called in to Ferguson’s office and told in a brief meeting he was being let go. He had known what was coming and had cleaned out his locker the night before, so he could disappear quickly without any goodbyes.