When Arsenal beat Manchester United 5-2 in 1960, was the match fixed?

I was lucky when I first used to go to Manchester United matches, over fifty years ago. Although the team was in the painful early stages of recovery from the Munich Air Crash they still often managed to play wonderfully expressive football in keeping with the finest traditions of the club.Take this description of United’s quicksilver style, written by ex-1930s Arsenal star Bernard Joy for a London paper prior to the Red Devils meeting the Gunners at Highbury in April 1960, under the heading ‘Busby Can Lead England Back To The Top’:

I was lucky when I first used to go to Manchester United matches, over fifty years ago. Although the team was in the painful early stages of recovery from the Munich Air Crash they still often managed to play wonderfully expressive football in keeping with the finest traditions of the club.Take this description of United’s quicksilver style, written by ex-1930s Arsenal star Bernard Joy for a London paper prior to the Red Devils meeting the Gunners at Highbury in April 1960, under the heading ‘Busby Can Lead England Back To The Top’:

Remembering Highbury

I always loved the thrill of anticipation when emerging from the Arsenal station to find the narrow streets and terraced houses blocking the view of Highbury until it suddenly loomed into view in all its refined Art Deco glory. On the day of that United match in April 1960 I was determined to see the haughty ‘ Marble Halls’ in the East Stand official entrance foyer, and I sneaked in nervously, expecting some uniformed commissionaire to toss me out on my ear like some grubby street urchin. I wanted to see the famous bust of former manager Herbert Chapman which sat on view in an illuminated niche. Chapman had been one of the innovative giants of inter-war football, first at Hudderfield Town in the 1920s and then Arsenal in the ’30s, making it entirely fitting that he was commemorated in bronze by Jacob Epstein, a world class modernist in his own right. This was just one more thing to savour before the match, which brought two undoubted giants of the game head to head.

Because of the grandeur of the stadium , with its AFC and ‘Gunners’ cannon insignia, I always thought of Highbury as steeped in history and tradition, yet in fact around the time I first went there its impressive East and West double-decker stands were little more than a quarter of a century old. In those days I usually stood on the raucous open terraces at the legendary Clock End or behind the goals on the covered North Bank, and the vista from either was magnificant.

Perhaps because the Arsenal team of the early Sixties was a shadow of its former self, there was sometimes a curious mood among supporters, a mixture of gloom, resentment, sombre passivity, frustration and resignation, suddenly dispelled with roaring cloudbursts of exultation when a Gunner put the ball in the back of the net. Having dominated football in the 1930s through to the early Fifties, Arsenal were now in something of a struggle against mediocrity, lingering season after season in the lower half of the table. So, as we came to the penultimate game in the 1959-60 season, having myself recently seen United thrash Fulham 5-0, comfortably beat Luton 3-2 and lose unluckily 2-1 to West Ham, each time displaying passages of play of the highest quality, I fully expected Arsenal to get a good going-over, as befitted their position seven places below United in the league table.

Basking in the expectation of victory is, however, in my long experience, never wise. And so it turned out on this occasion. Defeat I could take, but this was something different. This was the first time I had seen United at close quarters when they were playing badly. Very, very badly.

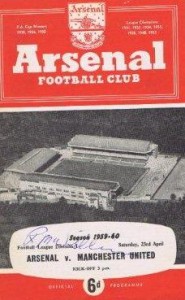

Saturday 23 April 1960: Arsenal 5 Man United 2

United were inconsistent throughout the ’59-60 season, scoring four or more goals on eleven occasions but also conceding three or more thirteen times, including a shocking 7-3 defeat by Newcastle in January, highlights of which I’d seen on TV. By the end of the season United had scored 102 goals in the league , a total they have only twice surpassed in their history, confirming what a potent attacking force they remained, led by Dennis Viollet with his record-breaking 32 league goals , followed by Bobby Charlton with 18, Alex Dawson with 15 and 13 from Albert Quixall. However, I knew the team could slip from sublime to slipshod in the twinkling of an eye, which I always put down to there being so many youngsters thrown in the deep end because of Munich. They never really challenged for honours in that season , ending up 7th in the table, but as the goals kept bombing in it seemed that at least progress was being made.

However, a match like this one at Highbury could only kick lumps out of this complacent attitude of long term optimism. United were not only dreadful, they appeared not even to care, which I simply could not comprehend as a 14-year old who thought teams all stuck together at all times and fought for each other whatever the outcome. Especially if they played for Manchester United.

It’s worth saying something about the Arsenal team that day, which despite their lowly league position featured some excellent players, including their top scoring centre forward David Herd, who’d got 14 goals in 31 appearances, prompting Busby to sign him for United a couple of years later. Then there was Wales international goalkeeper Jack Kelsey, plus fellow Welshman Mel Charles at right half , the beefy brother of the ‘Gentle Giant’ John Charles. Playing at centre half was the craggy, hard-tackling Scotsman Tommy Docherty, who of course became United’s manager in the 1970s.

United came running out for kick off looking full of shining confidence in their all-white, red-trim ‘away’ strip, but that was rapidly blown away when Danny Clapton gave the Gunners the lead after just six minutes. Mark ‘Pancho’ Pearson, always one of my favourites, equalised quickly with a cracker and I thought United were going to pull themselves together, only to concede again almost immediately through inside-left JImmy Bloomfield, who ended up with a well-deserved hat-trick. Johnny Giles made it 2-2 just before half time but in the second half Arsenal ran riot, rattling in three more goals as United cravenly fell apart, the last one coming two minutes from the end, scored by right half Gerry Ward. I was aghast, but at least my favourite, goalkeeper Harry Gregg wasn’t at fault for any of the five goals.

Matt Busby was later said to be furious at this sloppy, lacklustre performance, which I could fully understand. For me it had been a chasteningg experience, being only the fourth time I’d seen United in the flesh. It brought home to me just how far the Red Devils had to go before they would be seriously challenging for honours again and Bernard Joy’s fine words now rang very hollow.I felt flattened and disappointed as I made my way back to the Underground for my long journey home, surrounded by unusually jubilant Arsenal fans who were coming towards the end of a hard season on a high.

‘But, oh, how disappointing the Busby Boys! And how sad to see then indulging in shirt-pulling and over-robust tackling’ ( Daily Express, 25 April 1960)

‘But, oh, how disappointing the Busby Boys! And how sad to see then indulging in shirt-pulling and over-robust tackling’ ( Daily Express, 25 April 1960) According to the Dispatch Sports Editor George Rutherford, the United manager Matt Busby had ‘called on the Football League and the Football Association to investigate allegations that for weeks have been sweeping the country, directing suspicion at all the League’s 92 clubs.’

Then came the really disturbing bit for me, having myself sensed something was wrong at Highbury the week before: ‘He (Busby) hit out at rumour-mongers yesterday, after his club had become the latest storm-centre in a spate of vicious stories that matches are being “sold” to bring off betting coups.United were said to have “sold” their match against Arsenal at Highbury last week when they were beaten 5-2. Mr Busby’s answer to the whispers was “Utter nonsense” .He said : ” The situation has reached such a pitch that any team that loses is in danger of being accused of throwing a game.It is important to sift out the truth and put the public’s mind at rest. Unless it is checked the situation will only get worse. There should be an investigation. ” (The Sunday Dispatch, 1 May, 1960)

The report added that other managers were ‘gravely concerned’ too, including Arsenal’s George Swindin who said single-match betting was the real danger.

All agreed that urgent action was required to get the situation under control so the next season could start with ‘a clear conscience’

For days after this I would scan the papers for more information , expecting such scandalous allegations to attract enormous press coverage and lead to a full investigation, perhaps followed by criminal prosecutions. I dreaded the thought that my beloved United would be found to be involved in anything as underhand as match-fixing, whether bribing opponents or ‘throwing’ matches for money. But there was nothing. I never saw the issue mentioned again, and I assumed all was well, none of my heroes were tarnished. Then suddenly the whole subject flared up again in a much more substantial way some three years later, only this time United were not involved. At least on the surface.

The Sheffield Wednesday match-fixing scandal of 1963

I had long forgotten the shadow hanging over United from 1960 when suddenly a Sunday paper came out with a major scoop which didn’t involve United but raised the whole match-fixing issue on a much larger scale at the end of the 1962-63 season, when United were struggling against relegation in the league but heading for Wembley in the FA Cup.

A Strange Kind of Scandal

In 1991 the former United youth-team player Eamon Dunphy published his groundbreaking biography, A Strange Kind of Glory:Sir Matt Busby & Manchester United, which remains essential reading for anyone wishing to understand not just Busby and United but also the often harsh and sometimes ruthless world of football during that period . As an Irish kid trying to make his way in the game , Dunphy, who ultimately enjoyed a solid career at Millwall (as recorded in his brilliant earlier book Only a Game?), had a close up view of all the key players and the coaching staff at Old Trafford. That gives his writing a compelling immediacy, allied to his strong sense of history and trenchant political views. It was perhaps these qualities that made him the ideal ‘ghost’ to help Roy Keane write his even more controversial autobiography in 2002.

Anyway, Dunphy devotes a couple of measured but telling pages to the match-fixing issue, which prompted unwelcome reminders of my own suppressed anxieties on the matter. Placing the issue in the context of the troubled, faction-riven dressing room at Old Trafford in the early ’60s as United struggled to recover from Munich, he has this to say about what happened after the Sheffield Wednesday corruption was exposed:

‘The match-rigging scandal touched Manchester United when two Daily Mail journalists travelled to Blackpool, where the team were staying at the Norbrek Hydro, to confront United goalkeeper Harry Gregg and some of his colleagues with allegations that they had been party to the conspiracy. Busby was deeply shocked when confronted with the allegation that a small group of players had sold games. Unable to confirm the story, Busby persuaded the Daily Mail not to publish the allegations. He then convened a meeting of United’s players at which he warned that anyone caught or even suspected of match-rigging would be out the door. The matter ended there.’ (A Strange Kind of Glory, p.270-1)

Dunphy says that Gregg confirmed to him that there was substance to the allegations and that he was asked to throw matches several times between 1960 and ’63. He had refused to take part himself but told Dunphy that other players – whom he named – had thrown matches. One of those accused by Gregg admitted to Dunphy that there was a lot of discussion about fixing but insisted that nothing ever came of it. Others, ‘innocent of involvement’, Dunphy says, ‘acknowledge that on occasions there did appear to be something odd about United’s performances’ (Glory, p.271).

Admitting that it’s impossible to be certain on the basis of hearsay evidence which may be ‘contaminated by personal grievance’ Dunphy concludes with words that still strike a cold chill: ‘There is no doubt in my mind that Manchester United players did conspire to fix the result of at least three games during the ’60/ ’63 period. It is widely accepted within the game that those convicted in the ensuing (Sheffield Wednesday ) scandal were not the only prominent players involved in the match-rigging conspiracy’ (Glory, p.271)

Given that the only contemporary documentation specifying a particular fixed match was the Sunday Dispatch article which referred to United’s 5-2 defeat at Highbury in April 1960, I was forced to conclude that certain United players may indeed have thrown that match. The uncertainty about it all leaves a shadow over what should have been a relatively happy memory, even though United lost. Defeat I can take, but not selling your soul.

In the wake of Dunphy’s book there was some speculation about match-rigging , but no clear-cut allegations or names named which would have stood up in court, just rumours. The issue then died down again for another decade, until Dunphy’s chief source and old friend at Old Trafford Harry Gregg broke his silence.

Harry Gregg’s ‘Bad Bet’

The first United-related book I got was Harry Gregg’s autobiography, Wild About Football, published in 1961, still a treasured possession. Unsurprisingly it made no mention of match-rigging. He was a great hero of mine because of his bravery at the time of Munich when he went back into the burning aircraft and rescued people at great risk to his own life. He dislikes talk of his heroism, saying his actions were purely instinctive, although one can see from the recent alleged behaviour of the captain of a certain sinking Italian cruise-liner that instincts can take people in very different directions. Gregg was also my hero as a magnificent goalie, who I never tired of seeing in action with his flying leaps, fingertip saves and clattering encounters with sharp-elbowed centre-forwards. As soon as Harry published a new book, Harry’s Game:The Autobiography in 2002 I rushed out to get it, having forgotten all about the match-fixing controversy. The book is a good read, giving a sometimes painfully honest account of his conflicts with others in football – including clashes with colleagues at Old Trafford over corruption.

He devotes part of a chapter entitled ‘A Bad Bet’ to the match-rigging issue, broadly confirming Dunphy’s account. Harry says that the first time he realised there was something going on was when the young Irish full-back Joe Carolan came to ask for advice: ‘I was totally caught by surprise when Joe, who I must stress was not involved, asked for a quiet chat. We went to the boot room and he said: ‘Have they been to see you yet?’ I asked what about and he told me they’d offered him the chance to earn some extra readies on the fixed games and he didn’t know what to do.I replied: ‘They won’t come to see me,’ and advised Joe to ‘Go deaf, son’. (Harry’s Game, p.93-4)

I was pleased that Joe comes out of this well as he was a decent player in the first couple of seasons after Munich and never let the side down. He was playing at left back at Highbury on that fateful day in 1960, incidentally.

The next time the issue came up was when the Daily Mail reporters approached him at the Norbrek Hydro in Blackpool, as mentioned by Dunphy. They said they’d heard Harry had ‘stopped United throwing games’ and told him more of what they had discovered, which he found convincing, although he didn’t confirm anything that he knew, on the basis that wasn’t going to ‘throw teamates to the press pack’. Alarmed by the whole thing Gregg gathered the team together and told them what the Mailmen had told him and warned them all off: ‘I said I didn’t want anything to do with it’.

At this same time there was an Irish League v Football League representative match in Blackpool, covered for the Sunday Express by Spurs captain Danny Blanchflower, brother of United’s Jackie, who’d been badly injured at Munich. The two Mail reporters started deliberately talking loudly in front of the Irishman about match-fixing. Danny challenged them, saying, ‘I sincerely hope you’re not suggesting Tottenham Hotspur’. One hack replied, ‘No, but I’m afraid we can’t say the same for your brother’s club’. United’s Wilf McGuiness, on crutches following the injury that forced him to quit as a player, heard all this and angrily confronted the journalists, threatening to tell the boss, which suited them as they’d been trying to talk to Busby for two days.

Harry now raised the matter with trainer Jack Crompton (United keeper in the 1948 FA Cup Final) who clearly knew nothing, so he finally decided to take it up with Busby.He knocked on the manager’s door and went in: ‘Matt was sitting behind his big desk and I pre-empted the conversation by telling him there was no way I was going to give any names. He asked what I was on about and I said I didn’t mind having lumps kicked out of me, but I wasn’t sure who was playing for or against us . He ranted and raved, saying over and over: ‘I bloody knew’. And this was from a man not noted for his histrionics or foul language. Obviously, I’d merely confirmed what Matt already suspected.’ (Harry’s Game, p.95)

Matt received a letter of apology from the editor of the Daily Mail which he read out to the players , presumably as a stern warning about their future conduct. As Harry says, ‘It’s the only time , aside from Munich, I actually felt sorry for him. What a blow to your pride, to your respect for what had been built at Old Trafford’.

Gregg says that he got ‘incontrovertible proof ‘ of match-fixing in 1964 when he was dropping off a player in his car and the man, who was aggrieved about other matters ,admitted what he’d done and named the others involved.

‘I left Manchester United in 1966,’ Harry says, ‘and I know that after my departure games were thrown’ (Harry’s Game, p.96)

Question marks over Billy Meredith at City

United’s shrewd secretary-manager Ernest Mangnall promptly swooped to sign four of City’s best players, starting with Meredith in October 1906, although he couldn’t play until his ban expired in January 1907. Next United nabbed three more top quality players, including goal-scoring centre forward Sandy Turnbull together with Herbert Burgess and Jimmy Bannister. There was surprisingly little resentment from City towards United who were now in a strong position to challenge for silverware, winning the league twice in the next four years and the FA Cup in 1909.

The irony is that Meredith was extremely lucky not to have faced a lifetime ban for his attempted match-fixing. He never really gave a satisfactory explanation for what had gone on although he did produce a letter which appeared to show that whatever it was had been approved by the City management. His usual response when questioned about the attempted bribe was to laugh and change the subject.

There was an even more clear-cut match-fixing scandal at the end of the 1914-15 season, the last one before normal football was closed down for the duration of the world war. Saddled with debts after the building of the magnificent new stadium at Old Trafford in 1910 and sliding into mediocrity on the field, United were staring at relegation when they faced Liverpool on Easter Friday in April 1915. United beat Liverpool 2-0 with surprising ease, provoking ever more strident demands for a full investigation after strong indications that the match had been fixed. The upshot was that three United players, plus four from Liverpool and one from Chester were banned for life, including United’s Sandy Turnbull, Arthur Whalley and Enoch ‘Knocker’ West, whose goals had powered the team to their secong league title in 1910-11. West was the only United player who’d actually played in the offending match, which helped secure the Reds’ place in the top division, and he proclaimed his innocence for the rest of his life. Those protestations ironically probably ensured his ban was maintained long after the others had theirs lifted, in recognition of their service in the War.That reprieve was too late for Sandy Turnbull who was killed in action at Arras in 1917.

Enoch West’s ban was finally lifted after the Second World War in 1945, when he was 62 – still protesting his innocence.

Harry Gregg was playing that day, so let me leave the final words to him: ‘I always considered it a privilege to be paid for playing football. But with that privileged position comes a certain responsibility. Call me an idealist, but I firmly believe that each and every player, coach, and manager is duty bound to do their best. We owe it to the game, and to those not blessed with the skill and opportunity that takes you to the top’. (Harry’s Game, p.92)