‘The Death Match: The time FC Start defeated the Nazis at football’

Seventy-five years ago, on 9 August 1942, Kiev side FC Start defeated the Nazis at a game of football. The high of victory over their German oppressors was sobered instantaneously when the Gestapo arrested the entirety of the team in the following weeks. They had just defeated Flakelf, a German military football side consisting of Luftwaffe anti-aircraft gunners. There is no offering of an explanation for the arrests. Many of the players would lose their lives by the time the Red Army retook Kiev just over a year later. This was not how fairy tales were supposed to end.

A solemn reminder protrudes the Kiev skyline today, adjacent to the Start Stadium. Dilapidated high-rise flats swarm the surrounding area, reminiscent of the Soviet era. It is a statue of a naked man, defiantly shoving his fist into the sky whilst crushing the Nazi eagle underfoot. Here, ‘The Death Match’ heroes live on as martyrs amongst doting Kievans.

Football and history share a symbiotic relationship that draws nostalgic emotion and helpless attraction. The 1942 ‘Death Match’ epitomises this relationship. It is a story that fuses fantasy and reality, perception and imagination. You couldn’t write this stuff, but I’m going to give it a go anyways.

Every so often sport and history combine to produce events that eclipse their basic relevance, Jessie Owens at the Nuremburg Olympics in 1936, the Christmas day football match between the German and British soldiers during World War I. Etched on to this exclusive list is unquestionably the events of that hot summer evening in Kiev. The political and social magnitude of the event must not go a miss. Two opposing ideologies, two different social constructs, the oppressors versus the oppressed. Yet it came down to the fundamental basics, one team attempting to put a leather ball in a net more times than the other.

The Ukraine has historically been a nation passed from one ruler to the next, from the Mongols in the thirteenth century, to the Russians in recent centuries. Operation Barbarossa saw another invader make his claim. Hitler and the Nazis were quick to conquer, establishing a poverty stricken regimental regime. People resorted to the extremes for day to day survival. Chewing on the bark of trees for sustenance and consuming dirty German dishwater became a normal sight. Europe’s breadbasket was starving.

Hitler tasked Erich Koch, his assigned leader to Reichskommissariat Ukraine, with the instruction to create ‘Lebensraum’, or living space, for the superior Aryan race, at the expense of the sub-par Ukrainians. This policy did not discriminate. For the talented players of Ukraine’s most prestigious club, Dynamo Kiev, their days of fame were substituted for those threatened with starvation and death.

Nikolai Trusevich was born in the port city of Odessa in 1908. He was a goalkeeper well ahead of his time, confident with the ball at his feet and prone to starting many attacking plays. In today’s hipster footballing terms, Trusevich would be best known as a ‘sweeper keeper’. Considered the joker in the dressing room, he was adored by fans, for what his former teammate Anton Idzkovsky labelled as, “the Dance of the Goalkeeper”, which he executed in a serious demeanour, much to the hysterical amusement of his teammates.

A regular starter for the Dynamo Kiev side prior to the war, Nikolai had retracted to a life of poverty like so many of his fellow Ukrainians. However, when approached by Dynamo Kiev aficionado Joseph Kordik, his luck was about to change.

Kordik held the position of director at Kiev Bread Factory № 1 located at 19 Degtyarevskaya Street in the city. Upon hearing of the living conditions that Trusevich, one of his sporting idols, was subject to, he immediately offered him refuge with a job at the bakery. The shifts were long and strenuous but the job offered accommodation at the factory as well as safety from the threat of imprisonment, or worse, a fatal trip to Babi Yar where thousands of fellow Ukrainians had met their death at the end of German sub-machine guns.

After some hesitant deliberation, Trusevich was convinced by Kordik to track down some of his former Dynamo Kiev players and offer the prospect of employment at the factory. Trusevich would eventually assemble a very strong team under very surreal conditions.

The notorious Ivan Kuzmenko, nicknamed ‘Vanya’, spearheaded a multi-faceted attacking unit. He was one of the Soviet Union’s most talented forwards before the war, netting fifteen goals for Dynamo Kiev in the last season to be played. His rough and ready reputation hinged on stories such as that of him sewing three regulation footballs together after training, practicing his shooting with the extra weight to allow him to hit the ball all that harder.

Makar Goncharenko brought flair and raw talent to the wings. He had a disappointing start to his career, but once given the opportunity in the FC Start side, he quickly proved himself as one of the most talented players. So much was his confidence that he had kept hold of his boots after the Nazi invasion in anticipation that his ball skills would be required no matter who occupied the Ukraine.

In defence, the young Alexei ‘Sasha’ Klimenko, originating from a circus family in the Donbass region of eastern Ukraine, offered the protective base for the Start side. These respected players, in addition to the likes of Trusevich in goals, made them a formidable opponent for anyone.

The team, aptly named FC Start, began preparation for the return of a football league. The team consisted mostly of former Dynamo Kiev players as well as a handful from rival team, Lokomotiv Kiev. For the Nazi hierarchy, the decision was made that the reintroduction of football would boost morale amongst a depleted people, for even they had noticed that their ruling of Kiev’s inhabitants was not sustainable and perhaps a little too severe.

FC Start would begin their maiden season with a 7-2 demolition of Rukh, a team plagued with German sympathisers. This was followed up by a 6-2 victory over a Hungarian Garrison side. Their free-scoring attack was the talk of the city.

No more than three days later, a Romanian garrison side were the visitors. They would meet a similar fate, comprehensively beaten 11-0.

For the German authorities, Start’s run of form became a growing concern. The German influenced Kiev newspaper, ‘Nova Ukrainski Slovothey’, blatantly failed to replicate the growing success of FC Start in their match reports. After one particular match, the report overlooked the convincing score line in favour of FC Start and instead noted that the Start players were caught offside on numerous occasions. However, the paper credited the opposition for not being ruled offside, despite not scoring any goals or offering any attacking threat in the final third that would make being offside a possibility.

The deliberately priced five rouble fee on the gate offered little deterrence for the fans, much to the German’s annoyance. To place the ticket pricing into perspective, the average Kievan under German occupation could expect to earn 100 Roubles per month. One loaf of bread could cost up to half of that allowance.

An undefeated campaign prompted the German command to extend the season by one more game, to allow their pride of football, Flakelf, to play the team causing all the commotion, FC Start. The match took place on August 6, 1942. It was rumoured that Hermann Goring himself had overlooked the well being of the German side and had deemed their footballing credentials too important for them to be sent to the frontline. Nevertheless, on that humid summer day, the German defence was breached as easily as the Maginot Line two years prior. The verdict was a 5-1 victory for FC Start.

However, an embarrassed German leadership in Kiev refused to accept the result. Hitler’s claim that the Aryan race was superior in all aspects, including sport, was not to be disproved by eleven bakers from Kiev. The season was extended once more, and the rematch with Flakelf was scheduled three days later, only this time the German side had a handful of fresh new faces, cherry-picked from across Nazi occupied Europe. Defeat for them wasn’t an option.

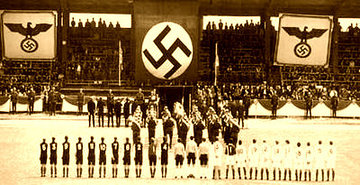

The posters sighted on buildings and street lights in the build-up to the contest were marked with the word, ‘revenge’. The anticipation and excitement resulted in a Zenit Stadium that was packed to capacity, although with the only seating being assigned to the large presence of high-ranked German command.

The term stadium was an exaggeration in itself. It was the sort of pitch that is commonly sighted strewn across the outskirts of small towns, inhabited only by uncoordinated and unfit part time brick layers for an hour and a half every Sunday morning. It was a venue not fit for the occasion, a fixture not fit for reality.

The realisation of the situation dawned on the players as they waited in the changing room. Go out and win at your own peril but be prepared to face the consequences, a train of thought that should never be present before something as innocent as a football match. The experienced and respected figures like Trusevich were able to calm the nerves and remind his teammates of the significance the game ahead held.

Tension engulfed the surrounding area. German Alsatian dogs patrolled the perimeter, accompanied by heavily armed soldiers. The fatigued FC Start team, exhausted from twelve hour shifts in the factory the previous day, didn’t leave anything on that stretch of grass, bringing a 3-1 lead with them into the interval.

The loyal following had broken into full voice, with unconfirmed rumours of anti-German chants. The emotion of the situation absorbed them. Two goals for either side in the second half gave FC Start a 5-3 win by the time the tentative referee blew for the full-time whistle.

FC Start had humiliated their oppressors. Hitler’s so called scientific truth behind the superiority of the Aryan race had been quashed during ninety minutes of football. Andy Dougan, author of ‘Dynamo’, referred to the match as one of “the most important in popular culture”. A game that would echo through eternity.

The arrest, interrogation and eventual death of many of these brave men would propel the story into the history books, as well as exposing it to far-fetched narrative. Despite Soviet history depicting the immediate slaughter of the FC Start team in the aftermath of the game, this was nothing more than a propaganda stunt.

Trusevich, Klimenko and Kuzmenko were three of the players executed by the Nazis as the tide of the war turned against Hitler. Their importance still lives on today. There is a tradition within Dynamo Kiev, by which newly married players place flowers at the foot of the statue outside the old stadium as a mark of respect. Although Andy Dougan says, “they were footballers first and representatives of a political ideology second”, there is no doubt that what they achieved for the people of Kiev and the Ukraine, represented a great deal more than a singular game of football.

A David versus Goliath story if you ever heard one.