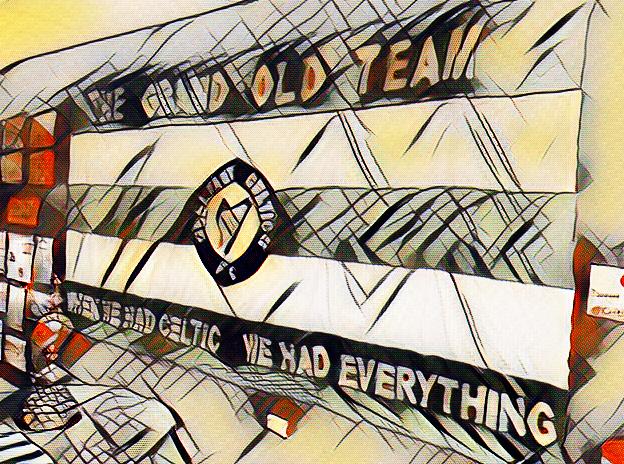

The Grand Old Team that Died: Belfast Celtic

“Even when we had nothing , we still had Celtic”

Near to the staunchly Republican area of the Falls Road in Belfast, there is a shopping development called the Park Centre which was constructed in the late 1990’s. Like many an urban shopping centre in any city in Britain, it is full of shops that have closed down and many of the clientele who frequent the area are representative of the benefits culture so despised by the right-wing press. However, this is not a place where you would choose to dress in a Union Jack T-shirt. As you enter, you might just notice a plaque that commemorates the fact that a famous football team once played here, nearly seventy years ago and was the pride of the Catholic population of Belfast.

This side was, arguably, the most successful British club team of the first half of the 20th century. Between 1936 and 1940 they won the Irish Championship five seasons in a row, achieving a league and cup double in two of those seasons. They only lost 14 games out of a possible 130.They won 42 trophies in 48 seasons. In their final sequence of games on a tour of the United States, they beat a full International Scotland side 2-0. Their fans called them the “Grand Old Team”. They were Belfast Celtic and football in Northern Ireland has never recovered from their loss.

Belfast Celtic were not just a power in Northern Ireland. They were one of the first British clubs to tour Europe in the 1910-1911 season. Whilst in Bohemia, they won 5 games out of 6. Newcastle United played the same teams and lost 5 out of 6! By the 1930’s Belfast Celtic were having regular successes against English league teams to the extent that many commentators thought that they would be able to hold their own in the English League.

In 1890, the Irish Football League commenced. At this time it was to be the League for all of Ireland although the original founder members came from around the Belfast area. Belfast Celtic were not amongst these clubs as they were not established until 1891. Linfield were the first champions in a league of eight teams. Linfield quickly became identified as the Protestant/ Unionist club wearing the same colours as Glasgow Rangers and with the same policy of not picking Catholics to play for the team.

The team called Belfast Celtic were created in the Falls Road area of Belfast, which is still to this day a staunchly Republican area. Bizarrely enough the formation of the club was partly due to that most English of sports, cricket. A local cricket team called Sentinel in August 1891 won a match against a touring team of some renown called The Model Stars. This led to the idea that there was an untapped mine of sporting talent that would benefit from the creation of a football team. This led to three local junior (non- league) sides, Clondara, Milltown and Millvale being merged to form the team that became Belfast Celtic to meet the sporting needs of the rapidly expanding Catholic population of the Falls Road area.

Not surprisingly, the club decided to model themselves on their Glasgow counterparts, Celtic and initially went under the same name, Celtic. They established links with the Scottish club who, in return, sent a generous donation to help the new club become established. The aim of the new club was to “imitate their Scottish counterparts in style, play and charity”. The original kit worn was green and white stripes, not hoops! The club continued to operate under the name of Celtic until 1901 when a new company was formed to run the club and as Celtic were already registered at Companies House, Belfast was now officially added to the club title.

Between 1891 and 1897, Belfast Celtic progressed through the ranks of the Irish Junior Leagues and were eventually accepted into the Irish League for the start of the 1896/97 along with the team from the North Staffordshire regimental army! The League only contained six teams for the season. During their last season as a junior club, their ground at Broadway, known for good reasons by the fans as “Boghead” had become unplayable. Therefore in their first season as a top-flight club, Belfast Celtic had to play all of their matches away from home. Their first game was a 1-0 defeat to Cliftonville. By now they were attracting a large number of followers and gaining a reputation as a Nationalist club. Their first visit to Linfield resulted in a 1-1 draw but in a pattern that was to recur throughout its existence the game was marred by pitch invasions and crowd trouble. For the first and only time in the history of the club, Belfast Celtic finished bottom, winning only one game 2-1 against Distillery. Even worse, the military team North Staffordshire finished above them.

For the 1897/88 season Belfast Celtic had their own ground alongside the city cemetery on Whiterock Road called Celtic Park. League fortunes quickly improved and the first league title was achieved in the 1899/1900 season. Sadly the number of incidents between rival fans was increasing and in 1900 the police placed notices at all the grounds of the clubs warning supporters about their behaviour. In 1901 the club purchased a ten-acre site on Donegall Road financed by selling 300 shares at £1 each. The new stadium was still called Celtic Park, but was known by the fans as Paradise after a Scottish journalist said their new home was like “moving from a graveyard to paradise”.

Between 1900 and 1915 Belfast Celtic established themselves in the League which now included both Bohemians and Shelbourne from the Dublin area. The next time they were to win the title was in the 1914/15 season. However, events off the field were posing a threat to the club’s very existence. During a cup game against Bohemians at Celtic Park, the Celtic forward Neal Clarke was sent off which caused a section of the crowd to invade the pitch and mob the referee who hid in the dressing room. As a result, the Irish Football Association suspended Clarke for ten months and ordered Celtic Park to be closed for a month.

The directors, already furious that Celtic Park was continually overlooked as a venue for hosting International and Cup matches, had decided they had been victimised enough. They met and decided to resign from the League. At this time they were one of the best-supported clubs in Ireland and the Irish Football Association could ill afford to lose such a source of revenue. They reversed both decisions and Celtic remained in the League.

In September 1912, over 20,000 fans turned up to watch Belfast Celtic play Linfield amidst the background of the controversial Home Rule Bill for Ireland. Almost 8,000 of the fans were supporting Linfield. As half-time commenced, fighting broke out in the so-called “neutral section” of the ground. As police intervened, fans began throwing stones at each other, then suddenly two shots were fired causing panic. Each set of fans thought they were under attack from the other and spilled onto the pitch. The referee had no choice but to abandon the game. Eventually, police restored order by marching the Linfield support away from the ground. Sixty victims of the clashes were admitted to Belfast hospitals, five of them suffering from gunshot wounds. Arguably, the whole affair had little to do with football. A simmering neighbourhood feud had existed between the Republican stronghold area of Falls Road and the hard-line Unionists of Sandy Row before either football club existed and attaching themselves to their respective football clubs allowed this animosity to flourish.

The Irish League was suspended during the First World War and did not resume until the 1919/20 season which ended with Belfast Celtic as Champions for the third time. They faced Glentoran, another team with a strong Unionist support, in a Cup semi-final at Cliftonville’s Solitude(brilliant name!) stadium in front of an estimated crowd of 18,000.Ironically enough the authorities decided to hold the match on St. Patrick’s day, a public holiday

The respective goalkeepers were actually brothers, Bertie and John Mehaffey. After eighty minutes, following a penalty area challenge, Belfast Celtic supporters reacted by invading the pitch as a large Sinn Fein flag was hoisted by their support. They quickly engaged in combat with the Glentoran supporters. Once again a shot was fired by a Celtic supporter and four fans suffered gunshot wounds. After the match, the battle spilled onto the surrounding streets. A certain George Goodman was arrested and charged with attempted murder. This was downgraded to “firing a weapon with intent to cause grievous harm”. He was found guilty and was sent to prison for eight years.

The streets of Belfast suffered from terrible outbreaks of violence during the summer of 1920 which almost made it impossible for normal life to continue. The Irish Football Association reluctantly gave Belfast Celtic, Bohemians and Shelbourne permission to withdraw from League football until the situation improved. It would take four years for that to happen and only one team would return.

When Belfast Celtic re-joined the League for the 1924/25 season it was with a completely different team as all the former players had moved to different clubs. The League had now increased to 12 clubs and after finishing second in their first season back, Celtic then proceeded to win the league four times in a row.

In 1934, the club appointed legendary Liverpool and Ireland goalkeeper Elisha Scott as player-manager. He had previously left Belfast Celtic for Liverpool in 1919. Although over the age of 40, he went on to gain three more caps for his country. He oversaw the most successful ever period in the club’s history as they established themselves as the dominant force in the league, winning the title an incredible five times in a row from 1935/36 until 1939/40. They went for spells of 31 and 37 games without defeat, attracting regular crowds of up to 30,000 to Celtic Park.

When football resumed after the Second World War, Belfast Celtic continued their stranglehold on the League, winning the Championship again in the 1947/48 season. They looked set to win the title again the following season but events were to take place on a football pitch that had never been witnessed before and were to lead to Belfast Celtic withdrawing from the League. Football in Northern Ireland has never been the same since.

In the 1948/49 season, a revitalised Linfield side were top of the table in December and posing a serious threat to Celtic’s title ambitions. The two teams met at Windsor Park on Boxing Day in front of a rabid crowd of over 25,000. One commentator recalled being at “the fuming cauldron of Windsor Park, watching 22 men from Linfield and Belfast Celtic being urged on to slaughter by many thousands of biased fans”. Until now players had not been directly affected by fan violence, that was about to change.

In the build-up to the game, Belfast had been awash with rumours of trouble at the forthcoming derby game. Players from Belfast Celtic claimed to have received letters warning them not to play at Windsor Park. Some of the team said there was a palpable sense of foreboding when they arrived at the stadium. In the matchday programme, the directors of Linfield said they were looking forward to a “grand sporting occasion”. Instead, they were to witness one of the most shameful episodes of thuggery in the history of British football.

As would be expected the match was a tough, uncompromising affair with no quarter given. Linfield’s Jackie Russell had already left the field due to an injury when just before halftime, Linfield’s defender Bob Bryson was carried off after a collision with Celtic forward Jimmy Jones. The halftime public address system reported that Bryson had suffered a broken leg, which immediately soured the mood of the home support, inflaming an already tense situation. Many Celtic players felt the announcer had deliberately incited the crowd. Linfield were already down to nine men. The score remained at 0-0.

Midway through the second half, the referee sent off Linfield’s Albert Currie and Belfast Celtic’s Paddy Bonnar. It was now eight against ten. With ten minutes remaining, Belfast Celtic were awarded a penalty which was converted by their captain Harry Walker. 1-0 to Celtic and with a two-man advantage. Incredibly though, just three minutes later, Billy Simpson hit a dramatic equaliser for Linfield and the crowd went wild.

According to some, several of the Belfast Celtic players were worried about the crowd reaction. As George Hazlett, a Celtic forward said later “when I saw the uniformed police, who were supposed to be neutral, throwing their caps in the air with delight, I realised we were not going to have much protection at the end of the game”.

On the final whistle as the players of Belfast Celtic were making their way to the pavilion, they were mercilessly attacked by elements of the Linfield support. Realising the danger, Celtic’s captain, Harry Walker ran to his goalkeeper, Kevin Mc Alinden and grabbed one of the iron bars that kept the goal nets in place to defend his friend. As a result of the manhandling he received, the keeper was out of football for two months. The Celtic players scurried back fighting off punches and kicks as they left the pitch. Everyone was relieved to have made the sanctuary of the changing room until someone said: “Where’s Jimmy ?” There was no sign of forward Jimmy Jones, who ironically was a Protestant. The team wanted to go out and look for him but were prevented from doing so.

On the final whistle, Jimmy Jones, who was a particular hate figure for the Linfield contingent, was hit on the back of the head. As he tried to escape, he was pushed over a wall onto the terracing, where some fans started to jump on his leg. Watching the match was the Ballymena goalkeeper Sean McCann who realising what was happening threw himself on top of Jimmy Jones to prevent further injury. Jimmy Jones later claimed that Sean had saved his life.

Jimmy Jones had his leg broken and was carried off unconscious on a stretcher. Later in hospital, he heard the doctors discussing the possibility of amputation. Fortunately, after a long recovery process and an operation that left one leg shorter than the other, he resumed playing for Glenavon but was never the same footballer. He was awarded £4,364 in compensation. Windsor Park was closed for a month.

The directors of Belfast Celtic were deeply concerned by the lack of protection provided by the officers of the Royal Ulster Constabulary and lack of support from the Irish Football Association. They lodged an immediate protest against “the conduct of those responsible for the protection of players in failing to take measures either to prevent the brutal attack or to deal with it with any degree of effectiveness after it developed”

However, behind the scenes, a more crucial decision was taken that they would withdraw from football at the end of the season. They felt that only by doing this could they prevent such scenes being repeated. At the end of the 1948/49, they withdrew from the League and never played a competitive game again, although they did undertake a final farewell tour of the United States that summer.

The Grand Old Team was no more and Irish Football has never recovered from the loss.

Yet, fittingly, the legend of Belfast Celtic lives on across the stadiums of England and Scotland. Fans of Glasgow Celtic and Everton amongst others often sing a song which commences,” it’s a grand old team to play for, it’s a grand old team to support and if you know your history”. Not many will realise that they are singing a tune that was regularly chanted at Celtic Park, home of Belfast Celtic from the 1920’s onwards!